90-Year-Old Japanese Internment Camp Survivor Writes Her Family’s Story of Hardship and Resilience

Evelyn Nagata loosely holds a surgical mask in her hands. Nagata recently turned 90 years old and has continued her work to chronicle her family’s history.

Local resident Evelyn Nagata is a survivor.

At nine years old, she was raised within the confines of a Japanese internment camp during World War II. Now, having turned 90 years old this past month, she endures a global pandemic while working to document the life she has lived and has borne witness to.

The Nisei woman – a second-generation Japanese American – has kept herself busy with a mission to finalize a family biography.

“I was the only one left to write it,” she said. “I asked my brother to write it but he didn’t, so I had no choice but to write it because it is a family story my daughter and my son and my grandkids need to know.”

Nagata feels there is one story in particular that speaks to her family history – one that is rooted in adversity and resilience.

She recalls a life interrupted in February of 1942 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which forced all people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, to be incarcerated in concentration camps. There were a total of 10 concentration camps that imprisoned 120,000 Japanese Americans, out of which two-thirds were born in America.

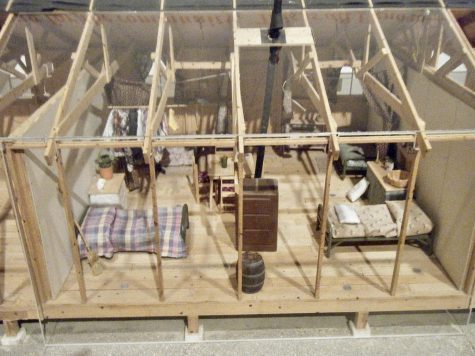

Vivid memories of guard towers occupied by rifle-bearing soldiers and fencing lined with barbed wire which surrounded the internment camps have

stuck with Nagata for over 80 years. She still pictures her temporary shelter in the Tulare Assembly Center beside a race track.

“We slept in horse stables and the walls had black tar paper. I remember that, but we just did the best we could.”

Shortly after her family’s time in Tulare, California, her family was moved to a permanent camp in Rivers, Arizona, known as Gila. Nagata recalls her family’s most memorable experience from Gila when Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited her older sister Kimii’s classroom.

“Mrs. Roosevelt had disagreed with President Roosevelt’s decision to incarcerate the Japanese from the West Coast, but apparently prejudice and pressures were too great from the surrounding agricultural community and other business circles,” Nagata recollected.

Nagata’s mother and father were forced to find work within the camps – her father worked as a night watchman while her mother was a kitchen employee in the mess hall. She remembers how her family worried if they would have a home or job to return to after the camp. Families were forced to abandon their homes and their businesses and only bring what they could carry. However, the restaurant her father had once worked at offered him ownership when his family returned – granting them a glimmer of hope upon being released to Chicago, IL.

Nagata’s husband Tad said that Japanese Americans were released gradually and only if they had a sponsor outside of the camps to take them in and guarantee them a job and a place to live. The Quakers were especially helpful in assimilating the Japanese Americans back into society.

Roughly 33,000 Japanese American men were drafted into World War II by a country that had unconstitutionally persecuted them. Tad was one of the many who gallantly served soon after being released from the internment camp.

In Nagata’s fourth grade classroom, she recalls learning the songs of the U.S. Armed Forces – from “Anchors Aweigh” to “The Marines’ Hymn.”

Despite the setbacks her family endured, Nagata found a life filled with love and learning beyond barbed wires. She reminisces about her time at Roosevelt University in Chicago, where she met her husband and felt she had known him from a “different lifetime.” She looks back fondly at her rewarding teaching career at a primary school in an underserved community on the south side of Chicago.

Nagata isn’t the only one with a success story to tell. The Nagata family as a whole has an extraordinary history.

Her brother Ben developed one of the deployment devices that was used in NASA’s Apollo missions. Her sister Kimii was pen pals with a descendant of founding father Alexander Hamilton while in the internment camps. Kimii received a brooch that once belonged to the founding father from her pen pal before evacuating the internment camp in 1944 as a symbol of peace and international goodwill.

The Nagata-Yamauchi family is now working to place what came to be known as the family’s “The Hamilton Pin” to be put on display in a museum for the Japanese American community and the world to treasure.

Nagata and her daughter Mari only learned more about this family connection two years ago.

“I just think it is so amazing that we have something from so long ago and yet it connects to our family’s history,” Mari said. “My cousin has kept in touch with descendants of Alexander Hamilton, and it’s just such a small world.”

During the Nagata family’s time in camp, Kimii wrote poetry that has been used to educate students about the internment camps. Her poem, “Be Like The Cactus,” was published in “Fred Korematsu Speaks Up” by Laura Atkins and Stan Yogi.

Nagata feels it necessary to capture her family’s story of resilience despite the jarring realities Japanese Americans faced. She reflects on the periods of violence she has witnessed in the United States and worries that the racial injustice and hatred her family once faced remains.

“I don’t know if the world has learned anything since then,” she admits.

When asked what kind of wisdom she can impart as a 90-year-old, she replied, “The only wisdom I can think of is let’s stop wars. No more war.”

Since moving to California 19 years ago, Nagata has made frequent visits and contributions to the Japanese American National Museum so that people can continue to learn about Japanese American history and the internment camps.

“The museum is a good place to learn about the culture and what they went through during wartime and the hardships they’ve been through,” Mari commented. “It’s important for people to know what happened and that this can happen to people of any background or race. It’s important for us to do our best to ensure that something like this never happens again. Make sure history doesn’t repeat itself.”

Beyond support for this historical museum’s preservation, Nagata has chronicled her own family history over the past two years to share stories dear to her. Her book is titled “Our Family Memoirs” and aims to educate future generations about the hard-working, honest people that came before. Within the next year, she looks to publish it to those she has devoted the work to first and foremost: her family.

Young at heart, Nagata is motivated by her ambitions to spend time with family, write and travel again. Until then, the Canadian Rockies and the Mississippi River will have to wait.

Smiling down at her hands, radiating a glow that many lose to the bitterness of time, she professed:

“Life is a dream.”

—

Evelyn Nagata is the grandmother of Nadia Razzaq.